Multiverse 2.357

paused to apply patchesSome image file formats like the ubiquitous JPEG standard, have file headers and metadata that can be scrutinized for signs of tampering in suspicious circumstances. There are increasing numbers of cases where malicious people take photographs of people and tamper with them, in order to create fake and compromising images for the purpose of blackmail or revenge. These file headers and metadata can sometimes reveal that the photos were tampered with.

The flip side of that is protecting your privacy by being aware of these identifiers. As a privacy conscious person, you should consider taking reasonable steps to avoid giving away any extra information when doing normal things, like posting a head shot on a dating website. It’s not just forensics specialists that are interested in this digital evidence, stalkers find it just as useful.

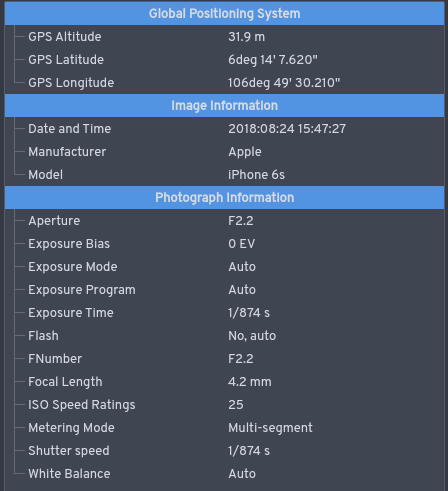

When looking at JPEG images, image sizes represent device capabilities and can distinguish between cameras that use different image resolutions. Metadata provides a wealth of device-specific and situational information. Some devices store thumbnail images along with the actual image data, but not all thumbnail images are created equally. These thumbnails have all the same sorts of identifiers as the original images. You can obviously control the size of an image you’re about to post onlineby cropping or resizing. Now let’s take a look at the metadata and what it reveals.

Devices that take real world inputs and digitize them typically embed metadata into the digital files produced. There is a standard for this called Exchangeable Image File (EXIF) format that is widely used in cameras, scanners and audio recorders, and by the camera in your smartphone. If you take a photograph with your camera, the visualinformation is stored in a file along with extra information including the type of camera used, the time and date, the geolocation of the image and quite a bit more.

This “metadata”, or data about the data file, is not encrypted and can be read by anyone. The good news, or bad news, depending on your perspective is that it can easily be removed, changed or faked. There are some “required” fields for whatever reason, but they are not the fields that give away the most sensitive information.

Note also that there can be several types of metadata in your photographs including XMP, IPTC data, and JPEG comments. It is also possible to embed data in the file itself using steganography – a topic we’ll cover in detail in future posts. Today we’re simply talking about data about the photo.

There are a variety of tools to read and modify EXIF data but our favorite is definitely Phil Harvey’s exiftool program. This is a command line utility that lists, modifies and removes fields. We’ll explore using this great tool from the command line and in python scripts, along with some similar tools in an upcoming post.

From a privacy perspective, the most potentially damaging data fields reveal your location, device details and the date and time the photo was taken. If you upload photos using your smartphone, you might want to install an app to strip EXIF data before posting. This is less than ideal OPSEC, since you are not cropping and saving in lossy format to reduce the quality of indicators like scratches or dust on the lens that allow companies like Facebook to identify you and your device.

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and many other large social media sites automatically remove EXIF data from photographs you upload, so your home location is not going to be accidentally revealed. But others don’t, and it’s not removed when you send media by email, share images using instant messenger apps, post your pics on a cloud storage site like Google Drive, share on an image site like Imgur or send files by SMS.

Removing EXIF data is easy on every major platform, including Android, iOS, Windows, OSX and Linux. Even if you put photos online after the fact, patterns of movement emerge from multiple images that might indicate where you live and work, where else you go and when, and predictable routines like weekly visits to specific places. Consider what data you’re permanently sharing with the entire Internet before sharing.

Your photos from the big televised sporting event might not need to have location stripped out, as it might be obvious where and when the photos were taken. For example if player names are visible on uniforms, it might be easy to tell in what game they were taken. But you might not want to disclose the type of device you are using, so removing EXIF data makes sense even in these cases.

If the photo is to be shared publicly, or stored in the cloud, removing the EXIF data is always the recommended behavior. There are just too many clues in this metadata. For example, if you cropped the image using image processing software like Photoshop, someone looking at it may be able to discern what version of software on which operating system you used. Unique photo identifiers are assigned commonly by smartphones, and can be used for determining in which order photographs were taken.

As far as altering the EXIF data goes, it is important to remove or change the EXIF data before the file is put in any public place, not after. This is because the versions can be compared using common forensic techniques and the change will be detected.

Remember the same EXIF data can be present in audio and video recordings too, not just images. This applies not only to data captured from your smartphone and camera, but also medical images and more. Every digital recording of real world data data should be checked before sharing online.

However if it’s important to you to leave evidence that supports a claim of authenticity, then you might want to leave the EXIF data as is. Consider for example, that instead of a sporting event your photos came from the scene of an auto accident or newsworthy event. If the purpose of a photograph is documenting something to be used as evidence, leave the EXIF data untouched, to avoid giving the appearance of tampering.

So when you really, really want to post that amazing photo you just snapped on your smartphone – consider removing the metadata first.

This is the third part in a series on cameras and photographs that started with Cameras, Photos and People and then proceeded to considertechniques for Camera Fingerprinting. Next, we’ll take a look at what we can expect in upcoming camera technologies.